Profiting from Information Asymmetry

How Quants Monetize Information Inneficiencies

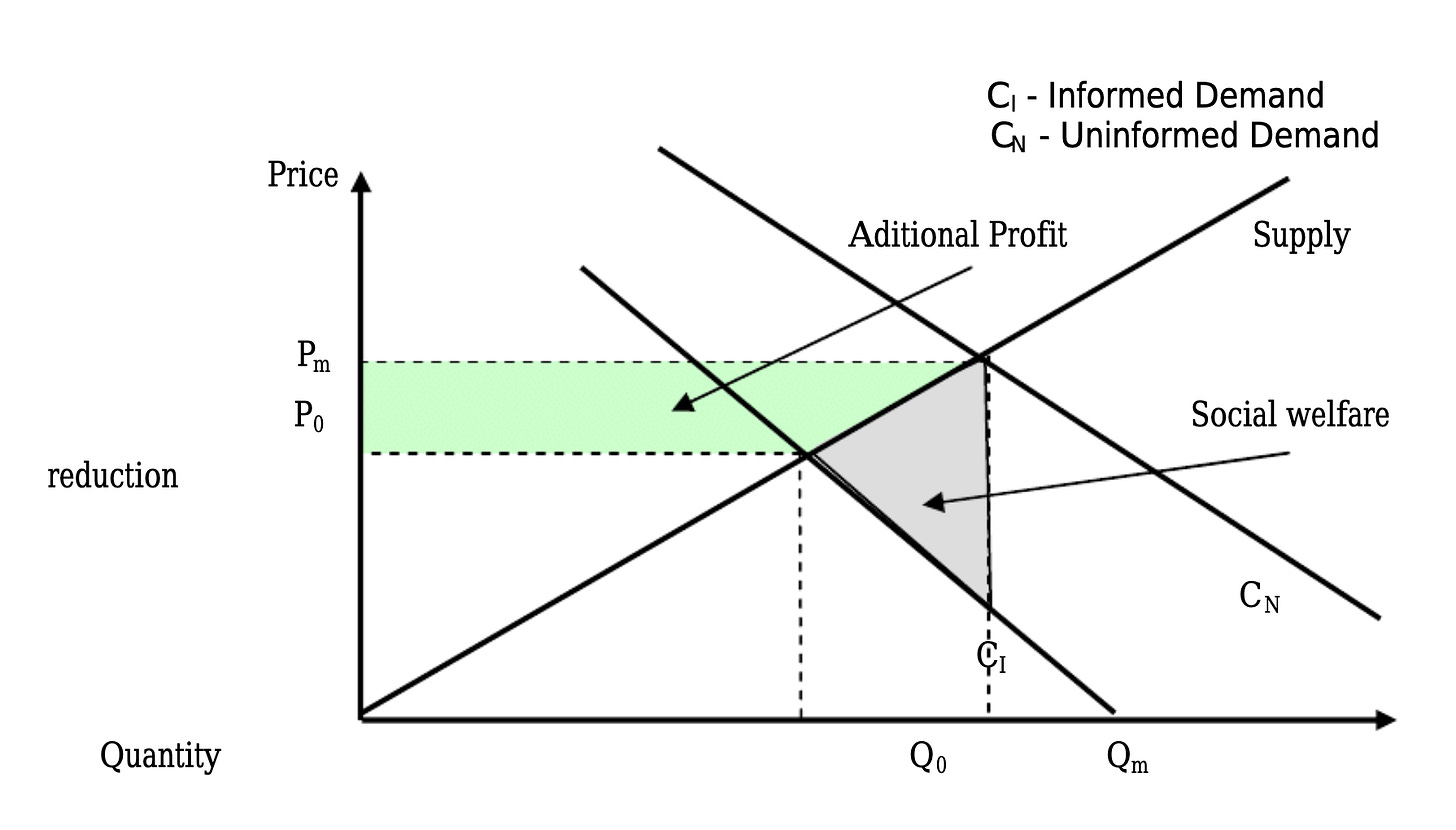

Markets sell you the story of efficiency. They say prices reflect all available information, that every trade is fair, and that alpha is just beta in disguise. But in practice, markets are messy ecosystems where information arrives unevenly, is interpreted differently, and is often flat-out wrong. This isn’t a bug. It’s the foundation of how money moves from the uninformed to the informed.

The truth is, most trading strategies—whether you call them “alpha” or “edge”—boil down to information asymmetry. Someone knows something first, or better. Someone misreads a signal. Someone assumes liquidity when there is none. The question for a quantitative trader isn’t whether these failures exist—they do—but how you can measure them, anticipate them, and systematically profit from the gap.

The Anatomy of Information Failure

Economists describe three classic flavors of information asymmetry:

Adverse selection: One party in a transaction has superior knowledge, and the other pays the price. Imagine a high-frequency market maker providing liquidity in a stock, unaware that an insider is trading ahead of an unexpected earnings warning. The insider unloads shares at an inflated price, and the market maker ends up holding toxic inventory once the news breaks.

Moral hazard: When hidden actions skew outcomes. In finance, this often means traders taking excessive risk because someone else bears the downside.

Signaling and screening: Firms or traders attempt to reveal or conceal information—earnings guidance, insider buying, unusual order flow.

In trading, adverse selection is the most direct money-maker. Spot the difference between informed and uninformed flow, and you’re no longer guessing; you’re playing weighted dice. That’s why high-frequency firms obsess over microsecond order flow patterns, why dark pool operators guard their flow data like gold, and why market makers with the sharpest filters can turn pennies per trade into billions over a year.